In real life, I'm a rather peaceful and gentle person, but I bring none of that to the chess board. When the clocks are started, I'm immediately transformed into a vicious predator. It's strange, but I've come to terms with my chess personality, and I don't try to avoid aggressive play.

That means that my games often see me attacking and my opponent defending. The most common scenarios are either me making a blunder due to over-confidence, or my opponent cracking under the pressure.

Sometimes, however, I face an opponent even more aggressive than myself, and that can lead to really weird games where most of the moves should objectively be classed as mistakes. Here's a recent example, enjoy! (I should add here that my opponent is a very gentle person away from the board.)

Me - N.N. (Open Tournament, 2024)

1. c4 e5 2. Nc3 Nc6 3. Nf3 Bc5 The first sign of aggressiveness. Instead of the standard move 3 ... Nf6, Black immediately takes aim at f2.

The cautious player now continues with 4. e3, making the Bishop look rather misplaced.

4. Na4 Chasing away the Bishop, but at a cost. The Knight has no future on a4, and must eventually return to c3.

4. Be7 5. g3 An attempt to steer into my normal Reversed Dragon, but that requires d3 to be played first. Now Black take the initiative with 5 ... e4 forcing the Knight back to g1, but instead:

5 ... d6 6. Bg2 h5 Black is eager to get a Kingside attack, and once again misses e4.

7. h4 Be6 8.

d3 Qd7 This looks dangerous, but it's not, unless White panics. White should now play Nc3, preparing a Queenside advance to discourage Black from castling long.

9. Ng5 Bxg5 10. Bxg5 (hxg5 was better) 10... f6 11. Bd2 O-O-O

Black wants to use all his pieces for his attack, but underestimates White's threats on the Queenside. 11 ... Nge7 preparing O-O would keep the game equal, but now White is clearly better.

12. b4

Nge7 Too slow. Nd4 followed by Bg4 was the only way to keep the attack going.

13. b5 Nd4 14. e3 Ndf5

Now White's attack breaks through before Black can organise their Kingside attack. Unless...

15. Qf3? White couldn't resist setting up a battery on the long diagonal. Rb1 followed by c5 would secure the win. Now Black could save the day by 15 ... c5, a nice multi-purpose move that stops White's c5 advance, and also defends b7. Instead, Black tries to dismantle the battery:

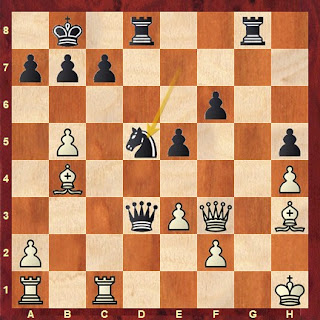

15... d5?? 16. Nc5 Qd6 17. Nxe6 Qxe6 18. cxd5

18... Nxd5?? Black is in in deep trouble, but Rxd5 would at least avoid losing a piece.

19. Bh3 Qd6 20. Bxf5+ Kb8 21. O-O? Wasting time. Qe4 would kept up the pace.

21... g5 This move is a ghost, because both players now foresee a terrible onslaught on the Black King, while in reality there isn't one. Unless White helps, which is what happened in the game. But first, some floundering where neither player finds the right moves.

22. Be4 Qe6 23. Bf5 Qd6 24. Rfc1

gxh4 25. gxh4 Rhg8+ 26. Kh1 Ne7 27. Bh3 Qxd3 28. Bb4 Nd5

White is still winning, but now it starts to slip.

29. Bf1? Qg6 30. Bg2?? Giving away the win. Bc4 was the only move.

30... Qf7?? Giving back the win. 30 ... e4 could save the game for Black. Surprisingly often a blunder is answered with another blunder, as this game demonstrates.

31. Rab1?? Another blunder, Rd1 was the right move. However, White still retains some advantage.

31... Rg4 32. a3? Now Black can take over the game with f5, but chooses a more "active" move:

32... e4?? 33. Qh3? (Qf5 wins) Rdg8 34. Rg1 Nxb4 35.

Rxb4 f5

White is a piece up, but how should White continue? The only move that promises winning chances is

Qh2, but that wasn't on my radar at the time. Instead, I went completely lost.

36. Rbb1?? Qf6?? 37. Bxe4?? Another triple blunder sequence! But now Black shook it off, and finished the game in orderly fashion.

37... fxe4 38. Rxg4 Rxg4 39. Rg1

Qxh4 40. Qxh4 Rxh4+ 41. Kg2 Rg4+ 42. Kh2 Rxg1 43. Kxg1 c5 44. bxc6 bxc6

45. f4 exf3 46. e4 c5 47. e5 c4 0-1

Takeaway

If you're an aggressive player, then go ahead and play aggressively. Just remember, you're increasing the randomness, and that means that both players will make more mistakes than in a normal game. So, against weaker players, it's safer to just wait out their mistakes before lashing out.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)